On Sunday and Monday I attended a Harvard Medical School annual review of obstetrics. One of the sessions that I was most eager to attend was the session on maternal mortality, and it did not disappoint. The most intriguing aspect was that the crisis in maternal mortality is almost exactly the opposite of what natural childbirth activists claim. Simply put, the crisis is not the over use of technology, but rather a mismatch between the number of pregnant women with pre-existing complex medical problems and the dearth of specialists and specialty units with the appropriate expertise to care for them.

The threshhold question, of course, is whether US maternal mortality is increasing. I’ve written about that many times over the years, and the speaker pointed out that it is probably not increasing; the apparent increase that we have seen (from 10.4-14.5/100,000 between 1990-2006) almost certainly reflects the ongoing efforts to appropriately classify deaths that occur in the wake of pregnancy. In other words, the rate of maternal death is not rising, the accuracy of our statistics is rising.

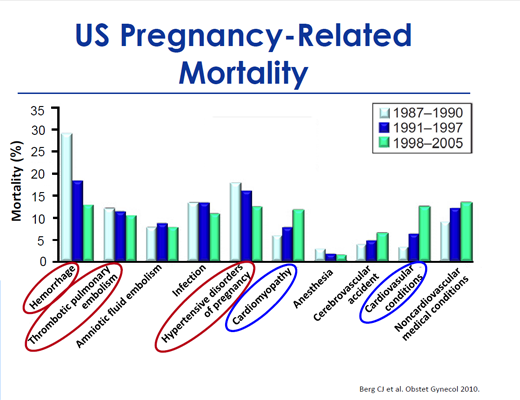

Be that as it may, maternal mortality is certainly not falling, and maternal morbidity (complications that do not result in death) is rising. Most importantly, the profile of maternal mortality is changing, as illustrated by the following graph from the paper Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005 (the markings were added by the speaker).

Note that the traditional killers of pregnant women (hemorrhage, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, blood clots) are being supplanted by new killers including pre-existing heart disease, cardiomyopathy of pregnancy (a weakening of the heart muscle) and other complex medical conditions. Indeed, while the death rate from traditional causes of maternal mortality has been steadily falling, the death rate from unusual causes has been steadily rising.

This almost certainly is a reflection of the increasing age and increasing obesity of pregnant women. So while complications from vaginal birth and C-section (infection, bleeding and blood clots) are still important causes of death, they are being supplanted by pre-existing medical conditions. We can and should work to decrease traditional causes of maternal death. For example, treating women with short courses of blood thinners around the time of surgery could drive down the rate of blood clots much further. However, the real crisis in maternal mortality is that we have not responded effectively to the increasing medical needs of pregnant women.

The speaker compared our response to maternal mortality with our response to perinatal mortality and raised an issue so obvious that I’m embarrassed that I hadn’t thought of it before. The dramatic decrease in perinatal mortality over the past 50 years reflects the creation of a specialty devoted to critically ill newborns (neonatology), specialty units for the care of critically ill newborns (neonatal intensive care units, NICUs), a rating systen for hospital nurseries (levels I, II, and III) to facilitate triage and transport of critically ill newborns to hospitals that have the experts and equipment to to treat them.

We have done nothing similar to address the increase in critically ill mothers. Although the number of pregnant women requiring intensive care is increasing, there are very few obstetric intensivists, very few obstetric intensive care units, and no rating system to facilitate transfer of critically ill mothers to hospitals that have the experts and equipment to treat them.

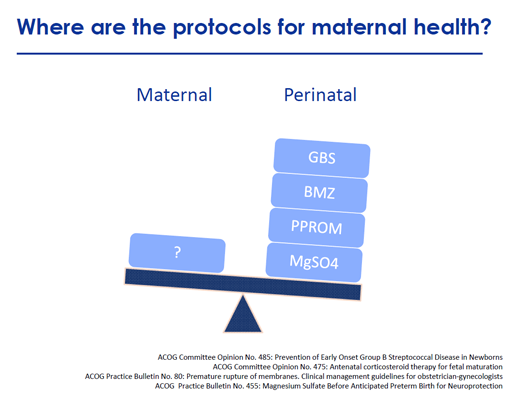

This image graphically represents the difference in our approach to preventing maternal mortality vs. preventing perinatal mortality.

In contrast to a wide variety of protocols defining best care practices for high risk perinatal complications, there are virtually none for high risk maternal complications.

The bottom line is that the solution to any crisis in maternal mortality is NOT indiscriminately decreasing interventions, since obstetric interventions are not the proximate cause of most cases of maternal mortality. It is imperative that we INCREASE our ability to identify critically ill pregnant women, transfer them to specialty obstetric units that have the personnel and equipment to manage their complex medical problems so we can apply MORE interventions to those complex medical problems, and identify best practices for managing complex medical conditions in pregnancy.

We may not have a crisis in maternal mortality yet, but if we fail to take these steps, we almost certainly will.