Another day, another bullshit breastfeeding study.

This one is Lactation Duration and Progression to Diabetes in Women Across the Childbearing YearsThe 30-Year CARDIA Study:

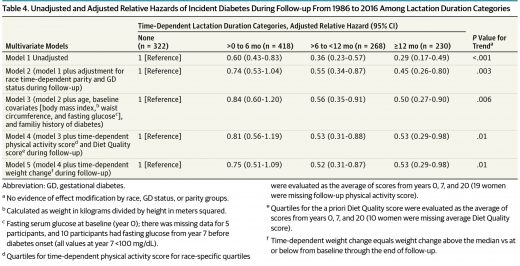

Among young white and black women in this observational 30-year study, increasing lactation duration was associated with a strong, graded 25% to 47% relative reduction in the incidence of diabetes even after accounting for prepregnancy biochemical measures, clinical and demographic risk factors, gestational diabetes, lifestyle behaviors, and weight gain that prior studies did not address.

In truth, the study didn’t show anything because it violated the most important requirement for a breastfeeding study; it failed to correct for maternal education and socio-economic status.

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]It’s the intellectual equivalent of claiming that Volvo ownership prevents maternal diabetes.[/pullquote]

How does this discredit the paper?

Breastfeeding in industrialized countries is closely associated with maternal education and socio-economic status. Adult onset diabetes is also closely associate with maternal education and socio-economic status. Unless the researchers correct for these factors (and they did not do so in this study), they end up demonstrating what we already know: the incidence of adult onset diabetes is a function of education and SES. It’s the intellectual equivalent of claiming Volvo ownership prevents maternal diabetes.

Researchers have confirmed the relationship between adult onset diabetes and socio-economic status in a wide variety of studies, including Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors looked at 23 studies:

Compared with high educational level, occupation and income, low levels of these determinants were associated with an overall increased risk of type 2 diabetes; [relative risk (RR) = 1.41, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.28–1.51], (RR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.09–1.57) and (RR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.04–1.88), respectively.

Similarly, there are a myriad of studies that confirm the relationship between breastfeeding rates and socio-economic status in industrialized countries. As an article in Quartz starkly illustrates, breastfeeding is basically a marker of education and income:

Why is it so closely associated with maternal education and socio-economic status?

Well-off parents have access to the infrastructure that supports breastfeeding: longer maternity leaves, jobs that allow for pumping breaks, the ability to hire outside help to support a new mother, and—perhaps most importantly—immersion in a culture that unconsciously views breastfeeding as a desirable status symbol and pressures them to continue to that hallowed six-month mark and well beyond.

Breast milk has become a luxury good, another example of what the sociologist Elizabeth Currid-Halkett calls inconspicuous consumption: the investments in intangibles like health and education that increase social capital for the modern wealthy. And because these costs are largely invisible, it’s easy to frame breastfeeding as a free good equally available to all. The truth is much more complicated.

How did the authors of the new paper account for the association between maternal education and income and both breastfeeding rates and rates of adult onset diabetes? They didn’t. That’s especially disconcerting when their own data (buried in Table 3) indicated a statistically significant difference in failure to graduate from high school [15% vs 13%; p <0.001] between those who developed diabetes and those who did not.

Adjusted models included covariables: examination years (time), race, family history of diabetes, baseline age, fasting glucose, BMI and waist circumference, time-dependent GD, parity and physical activity, and dietary quality score. Trend P values were generated from models of continuous time-dependent lactation duration. We evaluated potential confounders based on a priori hypotheses for selected baseline (BMI, fasting blood glucose and lipids, HOMA-IR, blood pressure, sociodemographics), and follow-up (smoking, dietary quality, physical activity, hypertension, medication use, and pregnancy outcomes) covariates.

Maternal education and income were ignored. And that makes the study worthless.

The authors blithely ignore their failure; they don’t deign to mention it in their self-reported limitations of the study despite the fact that it is the most critical — and inexcusuable — limitation of all.

The authors claim:

Our findings may have implications for social policies to extend paid maternity leave to achieve higher intensity and longer duration of breastfeeding. Second, increased allocation of health care resources to increase breastfeeding rates through the first year postdelivery may be offset by lower health care costs associated with prevention of chronic disease in women. It is also imperative to improve breastfeeding practices to interrupt the transgenerational transmission of obesity-related diseases. Lactation is a natural biological process with the enormous potential to provide long-term benefits to maternal health, but has been underappreciated as a potential key strategy for early primary prevention of metabolic diseases in women across the childbearing years and beyond.

Wrong! Their findings have no implications at all because they showed nothing beyond what we already knew: both breastfeeding and diabetes are associated with maternal education and income.

It’s yet another example that at this point breastfeeding research has become a self-reinforcing farce. Researchers assume breastfeeding is beneficial and then go searching for the benefits without bothering to correct for critical variables that are well known to be confounders for both health status and breastfeeding incidence.

That’s not science; that’s bullshit.