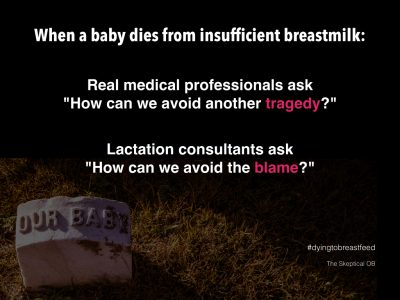

The impact of baby Landon’s death from insufficient breastmilk continues to reverberate around the world and lactation consultants continue to whine that such deaths are not their fault.

The brutal truth is that lactivists lie and babies die.

A new paper from the UK provides more tragic examples.

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Both symptoms and maternal concerns were routinely ignored.[/pullquote]

The paper is Neonatal hypoglycaemia: learning from claims by Hawdon et al. It’s a risk management paper, published to alert clinicians and managers to potential causes of lawsuits.

The authors found:

…In this 10-year reporting period, there were 25 claims for which damages were paid, with a total financial cost of claims to the NHS of £162 166 677 [over $250,000,000 at the 2011 exchange rate].

Hypoglycemia is low blood sugar. Severe hypoglycemia can lead to severe brain injuries. Two examples were included:

The child is severely disabled and requires 24 hour care support. It has not been established whether the brain injury will have any impact upon life expectancy although limited mobility and cognitive deficits would contribute to a loss of life expectancy and her medical needs for the rest of her life are likely to be complex.

And:

She is mobile indoors but cannot walk properly on uneven ground or on even ground for more than 200 metres. She requires assistance with dressing, cleaning after toileting and has to have food cut up. She has no sense of danger to herself or others, acts in a dangerous and destructive way and requires constant close supervision.

Most cases involved well known risk factors for neonatal hypoglycemia including low birth weight, poor feeding behavior, maternal insulin dependent diabetes and hypothermia.

In most cases insufficient breastmilk intake was the cause and poor feeding behavior was the primary symptom although there were a few cases where other factors were involved (one case of neonatal hyperinsulinism and one case of neonatal sepsis).

For 21/28 (75%) babies, it was the abnormal feeding behaviour which caused clinical concern. Of these 21 babies, 2 were also described as hypotonic, 5 also as cold, 1 also as irritable and 1 also as sleepy.

Eight out of 28 (29%) babies were described as hypothermic, either in isolation or in combination with poor feeding or being sleepy.

One baby was described as being hypotonic in isolation, and one baby presented with cardiorespiratory collapse.

For two babies presenting clinical signs were not documented.

In fully 36% of cases, mothers felt there was something wrong with the baby but could not get the staff to take their concerns seriously.

The authors provide four examples:

‘By the third day he was sleepy and disinterested in feeding. His mother asked for assistance to latch him onto the breast and voiced concerns that he was not feeding. His mother continued to alert staff to her problems in getting the baby to feed and the fact that he was sleepy.’

‘The mother informed the midwifery staff on the ward on a number of occasions on this and subsequent days following the baby’s birth, that she was concerned the baby was not sucking when feeding was attempted and she was concerned he was not feeding properly. These concerns were not heeded, resulting in the baby not being fed adequately and ultimately causing his collapse due to hypoglycaemia.’

‘The mother felt she had expressed concerns on multiple occasions about baby’s feeding technique both on delivery unit and on the ward but she felt she had not received adequate support. These concerns were not listened to.’

‘The parents brought the baby to the accident & emergency department with feeding problems and episodes of rolling his eyes. Seen by the paediatric team. After giving advice on feeding to the parents, baby was discharged home. The parents continued to be concerned and brought baby back to accident & emergency 3 days later. Blood glucose levels were not measured and parents told they could take him home.’

The authors issue a number of recommendations including:

Babies presenting with abnormal clinical signs, including abnormal feeding behaviour and hypothermia, must undergo detailed and documented assessment including measurement of blood glucose levels …

Maternal concerns, especially with regards to feeding, should not be discounted and should be followed by a detailed and documented history and assessment of the baby’s condition.

In the presence of clinical signs, once a diagnosis of hypoglycaemia is suspected or made, this constitutes a clinical emergency.

Babies with risk factors for neonatal hypoglycaemia or abnormal feeding behaviour should not be discharged from postnatal ward to the community without assurance that the milk intake is sufficient to prevent hypoglycaemia…

There’s a theme that emerges here and it is quite ugly: both symptoms and maternal concerns were routinely ignored. Mothers were reassured that their babies were fine when no clinical investigation had been undertaken.

That’s what happened to baby Landon, too. His mother recognized that something was wrong and her concerns were dismissed out of hand.

Keep in mind that this paper involves only injuries from hypoglycemia in which successful lawsuits were filed; there were undoubtedly additional cases. Moreover, it does not include lawsuits for damage resulting from neonatal dehydration, smothering in the mother’s bed and falls from the mother’s bed, all known to be associated with the relentless contemporary promotion of breastfeeding.

The real problem here is quite obvious; it’s the magical thinking that surrounds breastfeeding. That includes the belief on the part of nurses, midwives and lactation consultants that serious breastfeeding problems are rare, when, in fact they are common and that believing you can breastfeed is the key to successful breastfeeding.

So lactation consultants and others falsely reassure mothers that everything is fine when in reality the baby’s brain cells are dying. In other words, lactivists lie and babies die.