Did you have a C-section for “failure to progress”? It may have happened because the baby’s head did not fit through your pelvis, a condition known as cephalo-pelvic dysproportion (CPD).

CPD is far more common in humans than any other primates, because there are competing evolutionary pressures that have acted on the two most important parameters, the size of the mother’s pelvis (a big pelvis is good for childbirth, but bad for upright mobility) and the baby’s head (a big head is good for survival, but bad for childbirth).

Most people imagine that the pelvis is like a hoop that the baby’s head must pass through, and indeed doctors often talk about it that way. However, the reality is far more complicated. The pelvis is a bony passage with an inlet and an outlet having different dimensions and a multiple bony protuberances jutting out at various places and at multiple angles. The baby’s head does not pass through like a ball going through a hoop. The baby’s head must negotiate the bony tube that is the pelvis, twisting this way and that to make it through.

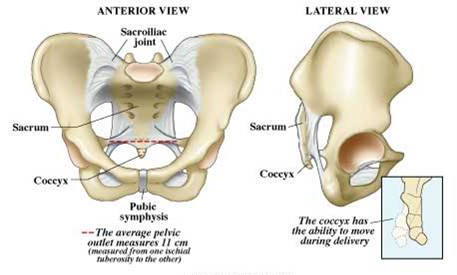

You can see what I mean in the illustration above (from Shoulder Dystocia Info.com). There are bony protuberances that jut into the pelvis from either side (the ischial spines) and the bottom of the sacrum and the coccyx, located in the back of the pelvis, jut forward. How does the baby negotiate these obstacles? During labor, the dimension of the baby’s head occupies the largest dimension of the mother’s pelvis. But because of the multiple obstacles, the largest part of the mother’s pelvis is different from top to middle to bottom. Therefore, the baby is forced to twist and turn its head in order to fit.

This illustration (from the textbook Human Labor & Birth) shows what happens. We are looking up from below and the fetal skull is passing through the mother’s pelvis. The lines on top of the skull demarcate the different bones of the fetal skull.

You can see that at the beginning of labor, the baby’s head is facing sideways; in the middle of labor, the head in facing toward the mother’s back; and after the head is born, it switches back to sideways and the shoulders come through the pelvis.

What does it mean when the baby’s head gets stuck? It can mean a number of different things. The pelvic inlet could be too small so the baby’s head never even drops into the pelvis. The ischial spines could stick too far into the pelvis and stop the head. The sacrum and coccyx could be angled too far forward and that could stop the head.

Clearly there is a great deal of potential for a mismatch between the size of the pelvis and the size of the baby’s head. Over time, babies have evolved so that the bones of the skull are not fused and can slide over each other, reducing the diameter of the head. This is called “molding” and accounts for the typical conehead of the newborn. But there is a limit to the amount of molding that the head can undergo and ultimately, the baby may not fit through.

The illustration above shows the baby’s head entering the pelvis in the optimal position, but babies don’t always cooperate. If the head is in anything other than the ideal position the fit will be even tighter. That’s why babies in the OP position (facing frontwards) and babies with asynclitic heads (the head titled to one side) are much more difficult to deliver vaginally. Their heads no longer in the smallest possible diameter. It’s like trying to put on a turtleneck face first of over your ear instead of starting from the back of your head. It’s much more difficult.

Although this is a more detailed explanation than that typically offered, it is still a simplified explanation. It does demonstrate, though, that many different variables are involved in whether a baby’s head will fit: the diameter of the pelvic inlet, the length and angle of the ischial spines, the angle of the coccyx, the position in which the fetal head enters the pelvis, the ability of the fetal head to mold to accommodate itself to the available dimensions.

Considering how many variables are involved, it’s not surprising that many babies simply do not fit. The real miracle is that most babies do fit. That was good enough to get the population to this point, despite the deaths of many babies and mothers childbirth. It’s no longer good enough, though because we want to save every baby and every mother. That’s why C-sections exist.

This piece first appeared in June 2010.