The road to hell is paved with good intentions … such as the intention to prevent complications by banning inductions prior to 39 weeks of pregnancy, also known as the 39 week rule.

I’ve been writing about the 39 week rule for years. I’ve argued that:

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Have we created a major disaster in an effort to fix a minor problem?[/pullquote]

1. Given that we know that the stillbirth rate is higher at 39 weeks than at 37-38 weeks, implementation of the 39 week rule would increase term stillbirths.

2. The attempt to reduce perinatal morbidity from early term delivery is fatally misguided. Sometimes the only way that you can prevent perinatal death is to deliver a baby early, which will result in increased morbidity like transient breathing problems and brief admissions to the NICU. An effort to reduce morbidity from early term delivery will NECESSARILY result in an increase in stillbirths.

It appears that this is precisely what has happened.

Changes in the patterns and rates of term stillbirth in the USA following the adoption of the 39-week rule: a cause for concern? was presented at the recent annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

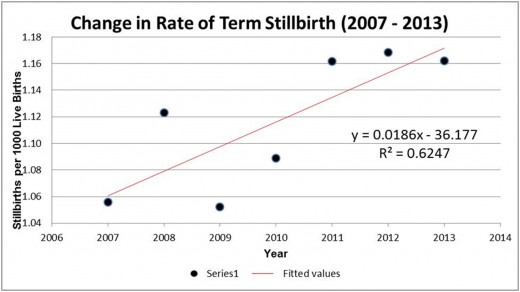

Between 2007 and 2013 in the USA, the implementation of the 39-week rule achieved its primary goal of reducing the proportion of term births occurring before the 39th week of gestation. During the same period the rate of USA term stillbirth increased significantly. Assuming 3.5 million term USA births per year, more than 300 more term stillbirths occurred in the USA in 2013 as compared to 2007. This study raises the possibility that the 39-week rule may be causing serious unintended harm. Additional studies measuring the possible impact of the implementation of the 39-week rule on major childbirth outcomes are urgently needed. Pressures to enforce the 39-week rule should be reconsidered pending the findings of such studies.

As lead author James Nicholson, MD commented to Medscape:

This study raises the possibility that the 39-week rule may be causing serious unintended harm.

Term stillbirth is clearly one of worst obstetrical outcomes, and it occurs with relatively high frequency — in one per 1000 deliveries that reach 37 weeks …

Unless or until high-quality research is published that proves that the 39-week rule does not increase term stillbirth rates, the forced imposition of the 39-week rule should be immediately reconsidered.

The authors presented an very impressive graph of stillbirth rates:

This increase in stillbirths neatly matches the change in gestational age at delivery that occurred during the same time period; the proportion of births at 38 weeks steadily declined while the proportion of births at 39 weeks steadily increased.

The data presented by Dr. Nicholson and colleagues seems pretty damning. In an effort to reduce mild, transient complications in newborns, we’ve let nearly 300 babies die stillborn each year, exactly as critics of the 39 weeks rule such as myself predicted.

BUT there’s an extremely important caveat. Two critical pieces of data are missing and without them, it’s difficult to draw any conclusions at all.

What’s missing?

While the increase in the stillbirth rate between 2007-2013 is impressive, it doesn’t mean much unless we know that the trend in stillbirth rates was before 2007. If stillbirth rates were steady or dropping in the years prior to 2007, there would be a very strong case that the 39 week rule is the cause of the observed increase in stillbirths. But if the stillbirth rate were rising in the years prior to 2007, we would have to postulate a different reason for the increase in stillbirth.

The other critical information that’s missing is the perinatal mortality rate. If the 39 week rule is responsible for the increased stillbirth rate, the perinatal mortality rate should have risen, too. If it didn’t rise, we’d have to consider the possibility that the babies who were stillborn would have died anyway after they were born and that the 39 week rule has merely changed the timing of death, not the eventual outcome.

It’s difficult to find these missing pieces of data because the authors used a custom database to determine the term stillbirth rate and it may not be comparable to the rates published by the CDC for the same years. I left a question on the Medscape article asking if some of that data could be provided. Without it, it’s nearly impossible to determine whether the authors’ contentions are true.

If 300 babies a year are stillborn who would have lived in the absence of the 39 week rule, we have created a major disaster in an effort to fix a minor problem. But until we learn the overall trend of stillbirths prior to 2007 and the perinatal mortality rates from 2007-2013, there’s no way to know for sure.