It sounds spectacular. The headlines in The Guardian are typical, Breastfeeding could prevent 800,000 child deaths, Lancet says:

If almost every mother breastfed her children it could prevent more than 800,000 child deaths a year, yet governments are failing to promote and support breastfeeding, with rates remaining far below international targets, new research has found.

Poor government policies, lack of community support and an aggressive formula milk industry mean breastfeeding is not as widespread as it could be, according to a two-part Lancet breastfeeding series published on Thursday.

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”#F90207″ class=”” size=””]Countries with the highest infant mortality rates have the highest breastfeeding rates.[/pullquote]

It certainly seems plausible since breastfeeding is known to prevent diarrheal illnesses and colds and since formula prepared with contaminated water can be deadly. I had no reason to doubt the claim when I started reading the main paper Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect.

According to the authors:

Our meta-analyses indicate protection against child infections and malocclusion, increases in intelligence, and probable reductions in overweight and diabetes. We did not find associations with allergic disorders such as asthma or with blood pressure or cholesterol, and we noted an increase in tooth decay with longer periods of breastfeeding. For nursing women, breastfeeding gave protection against breast cancer and it improved birth spacing, and it might also protect against ovarian cancer and type 2 diabetes. The scaling up of breastfeeding to a near universal level could prevent 823 000 annual deaths in children younger than 5 years …

But the more I read, the less convinced I became.

Why?

Countries with the highest infant mortality rates have the highest breastfeeding rates.

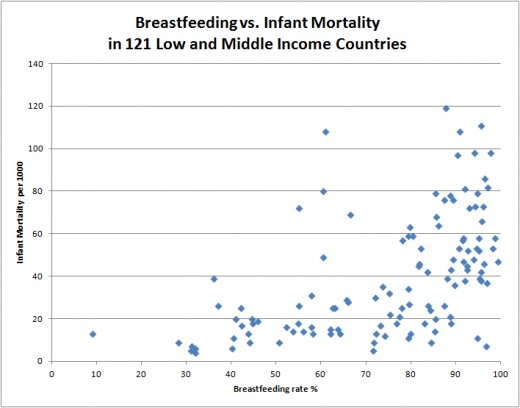

I created this scatter plot of 121 low and middle income countries by comparing breastfeeding rates at one year (found in the supplementary material) and infant mortality rates (deaths from birth to 1 year, UN data).

As you can see, there’s no relationship between breastfeeding rates and infant mortality rates. Indeed, the countries with the highest rates of infant mortality often have the highest breastfeeding rates.

Why doesn’t breastfeeding have an impact on observed infant mortality?

Part of the reason is that the benefits of breastfeeding are quite small. Over 800,000 deaths prevented is a great thing, but when you consider that over 135,000,000 babies are born around the world each year, the deaths prevented present 6 babies per 1000. That’s too small to be reflected in country wide infant mortality.

So if infant mortality rates don’t change with breastfeeding rates, how did the authors reach the conclusion that 800,000 lives could be saved if all mothers breastfed? They extropolated from small studies and made a myriad of assumptions in doing so. It seems to me that many of these assumptions are simply wrong, rendering the authors’ conclusions unlikely to be true.

I’m no statistician and I haven’t read all the studies that the authors rely upon, so if I’m making mistakes with my analysis please let me know, but here are my concerns.

1. The authors assumed that findings of small studies could be extrapolated to entire nations. But each study had its own parameters and confounding variables and therefore might not be generalizable.

2. The authors assumed that substantial numbers of babies are dying from formula or contaminated formula itself. But the scatter plot suggests that there are other factors responsible for the bulk of infant deaths. These could be malnutrition (of mother and/or baby), infectious diseases that cannot be prevented by breastfeeding, civil unrest, etc. For example, promoting breastfeeding is not going to save a baby whose mother dies of malnutrition leaving him without any source of food.

3. The authors assumed that the lifesaving benefits of increasing the breastfeeding rate would be evenly distributed over populations, but that can’t possibly be true. When a country has a high infant mortality rate and also has a breastfeeding rate of 97% of 1 year olds, there’s no room to raise the breastfeeding rate.

4. The authors ignore history. There was a time when 100% of infants were breastfed … and the infant mortality rate was astronomical because the benefits of breastfeeding are really limited.

There’s nothing wrong with promoting breastfeeding. But there is something wrong with making spectacular statements about breastfeeding saving hundreds of thousands of lives in the absence of population data to support it. Small scale studies can provide valuable insights, but they can’t replace real world experience. In the real world, breastfeeding rates don’t seem to have much impact on infant mortality rates at all.

It would be interesting to model how many lives could be saved by other measures such as water filtration and food donations; those have the added benefit of being able to save lives of older children and adults, not just infants. I suspect that something like water filtration could save far more lives than promoting breastfeeding. It’s much cheaper to promote breastfeeding though than to provide, run and maintain water filtration technology.

Where does that leave us? It leaves us telling poor women that they could solve their own problems by breastfeeding, and patting ourselves on the back for our insights. Meanwhile babies continue to die in droves from causes that have nothing to do with breastfeeding at all.