Breastmilk is amazing?

Possibly, but not in the ways that lactivists imagine.

Angela Garbes insists The More I Learn About Breast Milk, the More Amazed I Am. But Garbes doesn’t even get the basic facts about breastmilk right, let alone more dubious claims.

It contains all the vitamins and nutrients a baby needs in the first six months of life …

Wrong.

Breastmilk does not contain enough Vitamin K to prevent deadly hemorrhages of the newborn, and it doesn’t contain the iron that babies need.

[pullquote align=”right” color=”#bf0e0e”] There was no difference in immune cells in breastmilk of mothers whose babies had infections.[/pullquote]

According to Hinde, [Katie Hinde, a biologist and associate professor at the Center for Evolution and Medicine at the School of Human Evolution & Social Change at Arizona State University] … If the mammary gland receptors detect the presence of pathogens, they compel the mother’s body to produce antibodies to fight it, and those antibodies travel through breast milk back into the baby’s body, where they target the infection.

Not exactly.

According to Bode et al. in It’s Alive: Microbes and Cells in Human Milk and Their Potential Benefits to Mother and Infant:

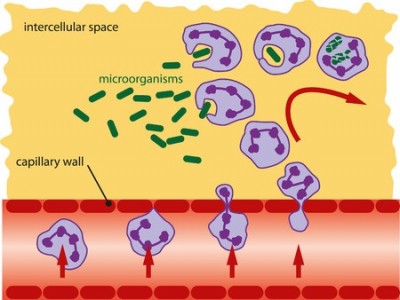

Recently, Hassiotou et al. (5) showed that a low proportion of human milk immune cells (0–2% of total cells) exists in the milk of healthy mother/infant dyads during established lactation. Immune cell numbers increase rapidly in response to infection of the mammary gland and other maternal infections, as well as infant infections, returning to baseline amounts during recovery.

So in healthy mother/infant dyads, breast milk has few white cells. But if the mother gets mastitis, the proportion of white cells rises. That’s hardly surprising. White cells race to the site of any infection. We have a name for large collections of live and dead immune cells and the debris of the bacteria they have destroyed. It’s called pus.

Indeed, in severe cases of mastitis, abscesses (collections of pus) can develop in the breast and may require surgery to treat them.

Does the breast respond to infant infections? It does if both mother and baby have the same infection. For example, a baby can develop thrush (a yeast infection of the mouth) and the mother can get a yeast mastitis as a result, and vice versa.

But what about infections restricted to the infant? The claim that infant infections affect the immune cells in breastmilk comes from this paper, Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. The authors note:

A small increase in breastmilk leukocyte content was also observed when only the infant had an infection, while the mother was asymptomatic (P=0.046).

The authors defined statistical significance as p<0.05.* Although that means that the result is significant, the paper itself shows that there were only 3 babies in that cohort and only 28 in the normal cohort. It’s unclear if the study is adequately powered and the authors never did a power calculation.

Therefore, there was NO DIFFERENCE in the level of immune cells in breastmilk of asymptomatic mothers whose babies had infections.

This is illustrated in a chart excerpted from the paper:

The red arrow shows the difference in immune cells in breastmilk from an infected breast. There’s clearly a large difference. But there’s no change when an infant has a cold (green question mark) and an insignificant difference when an infant has measles (blue arrow).

Hinde claims:

Everything scientists know about physiology indicates that baby spit backwash is one of the ways that breast milk adjusts its immunological composition. If the mammary gland receptors detect the presence of pathogens, they compel the mother’s body to produce antibodies to fight it, and those antibodies travel through breast milk back into the baby’s body, where they target the infection.

But what do the data really show?

Returning to the leukocyte response paper:

In addition to breastmilk leukocyte response to maternal/infant infection, a less consistent but often significant humoral immune response was observed…

The authors make no mention of what proportion of these infections were infant infections, so there’s no way to know if the observed response is solely due to maternal infection and whether infant infection elicits any humoral immune response at all.

So is there really spit backwash?

If there’s NO DIFFERENCE in levels of immune cells in breastmilk of mothers whose babies are sick and no evidence demonstrating a humoral response to infant infection, there NO EVIDENCE that breastmilk changes in response to a baby’s illness, and NO REASON to postulate fanciful mechanisms for events that don’t happen.

Is breastmilk amazing? Possibly.

Sure the number of immune cells changes dramatically in response to an infection in the breast. That’s pus. But breastmilk DOES NOT change in response to infant illness.

The only thing that’s amazing is how willing lactivists are to stretch the truth in a never ending effort to convince us that breastmilk is amazing.

*In my original analysis I failed to note that the authors used a p value of <0.05, which means that a result of p=0.046 is statistically significant.