Why are proponents of delayed cord clamping so sure that it has benefits for term infants despite all the scientific evidence to the contrary?

In part it’s because they have extrapolated inappropriately from existing science. It has been known for some time that delayed cord clamping is beneficial for premature infants. How? Many premature infants develop anemia known, not surprisingly, as anemia of prematurity. As this article on Medscape explains:

All infants experience a decrease in hemoglobin concentration after birth… For the term infant, a physiologic and usually asymptomatic anemia is observed 8-12 weeks after birth.

Anemia of prematurity (AOP) is an exaggerated, pathologic response of the preterm infant to this transition…

AOP spontaneously resolves in many premature infants within 3-6 months of birth. In others, however, medical intervention is required.

Delayed cord clamping provides an auto transfusion in the moments after birth, thereby decreasing the chance that a premature infant will need a blood transfusion for severe anemia.

But term infants don’t suffer from anemia of prematurity, so there’s really no reason to believe that delayed cord clamping is beneficial for them.

However, the real reason for believing that there are purported benefits is that proponents of cord delayed cord clamping come from a midwifery tradition of reflexive defiance. Simply put, many midwives operate on the premise that whatever obstetricians do is “unnatural” and therefore doing the opposite must be better. Not surprisingly, then, the “benefits” of delayed cord clamping were fabricated from whole cloth by a midwife. According to CNN:

What started as a grass-roots movement by UK midwife Amanda Burleigh nearly a decade ago, has recently grabbed the attention of medical doctors around the world. “I wanted to find answers to why so many children, including mine, my friends’ and my colleagues’ appeared to have additional learning and health needs, especially the boys,” said Burleigh. So she started reflecting on her own practice as a midwife.

“I began to question why we were trained to cut the umbilical cord immediately after a baby was born,” said Burleigh. “I then started to explore my theory that there must be a link to a child’s health based on when the cord is cut.” Her curiosity grew into a movement.

In other words, with absolutely no evidence, Burleigh spun a fantasy that her children’s learning and health needs were due to the evil acts of obstetricians, specifically immediate cord clamping.

In the intervening decade there have been numerous studies that were supposed to show the benefits of delayed cord clamping in term infants, but ended up showing nothing much at all.

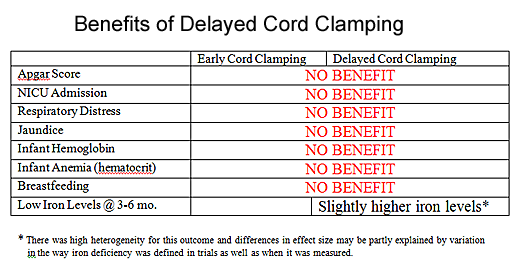

Two years ago I wrote about the last study to receive substantial media attention in Delayed cord clamping: much ado about nothing, and I included a handy chart:

So the only “benefit”was slightly higher iron stores (a laboratory value), one that has no clinical effect and probably has no clinical significance.

But that hasn’t stopped proponents of delayed cord clamping from continuing their desperate search for benefits.

The latest effort comes from Sweden, and the scientists who conducted the study promoted it breathlessly … as nearly all scientists promote their work whether it is high quality or useless.

From the CNN article:

“It’s incredible to see what a difference an extra three minutes and one-half cup of blood can have on the overall health of a child, especially four years later,” said Dr. Ola Andersson, lead author of the study and a pediatrician at the department of women and children’s health at Uppsala University in Sweden. “This is very promising, but larger studies are necessary,” said Andersson.”

Not exactly.

What was the study, Effect of Delayed Cord Clamping on Neurodevelopment at 4 Years of Age; A Randomized Clinical Trial, looking for?

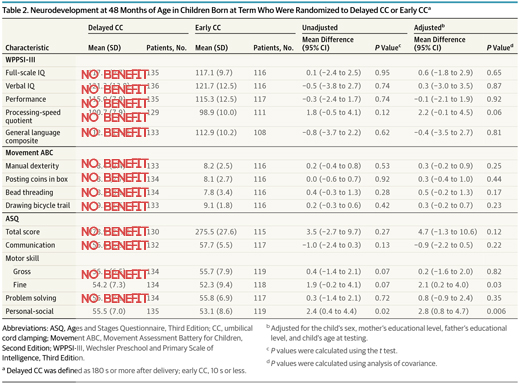

The main outcome was full-scale IQ as assessed by the WPPSI-III.

What did the author find?

As the chart below demonstrates, they found that delayed cord clamping had no benefit on IQ. Specifically, there was no benefit on full scale IQ, no benefit on verbal IQ, no benefit on performance, no benefit on processing speed and no benefit on general language composition.

But wait!

Fine-motor skills were assessed by the manual dexterity area from the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition (Movement ABC), which includes 3 subtests: time for posting coins into a slot (both hands), time for bead threading, and drawing within a bicycle trail…

Delayed cord clamping had no benefit on any of these tests of manual dexterity.

So delayed cord clamping had no benefit on IQ and no benefit on manual dexterity.

But wait! All was not lost:

Parents reported their child’s development using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Third Edition (ASQ) 48-month questionnaire, which was translated into Swedish … The ASQ contains 5 subdomains: communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving, and personal-social …

On 2 of those 5 parent assessments of their child, fine motor and personal-social, the delayed cord clamping group had statistically significantly better scores.

What does that mean? Absolutely nothing!

In reality, this study demonstrates that delayed cord clamping in term infants has NO appreciable benefits.

The study was conducted to determine if delayed cord clamping has an effect on IQ and found that it doesn’t. The the authors looked at objective tests of manual dexterity and also found no difference. Then they looked at parental assessments of child performance and found a statistically significant difference between in two subsets, but at no point have the authors demonstrated that the small sample of 263 children (which represented only 2/3 of the children originally enrolled) has enough statistical power to be valid.

In other words, the authors failed to find any meaningful benefit in neurodevelopmental outcomes caused by delayed cord clamping.

Contrary to Dr. Andersson’s assertion, the only thing incredible about this study is how brazen the authors are in claiming that their findings are incredible when, in fact, they merely highlight the increasingly desperate efforts to find some benefit, no matter how arcane, from delayed cord clamping in term infants.