Not surprisingly, the authors of a new study on breastfeeding and IQ led with the information likely to generate the best headline, Breastfeeding ‘linked to higher IQ’:

A long-term study has pointed to a link between breastfeeding and intelligence.

The research in Brazil traced nearly 3,500 babies, from all walks of life, and found those who had been breastfed for longer went on to score higher on IQ tests as adults.

Experts say the results, while not conclusive, appear to back current advice that babies should be exclusively breastfed for six months.

But the study, Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil, which shows that breastfeeding might have an impact on IQ of up to 3.76 points also demonstrates that just about anything else has a far greater impact on IQ than breastfeeding.

Consider this graph showing the impact of breastfeeding on IQ stratified by family income:

The graph shows several interesting things:

1. Breastfeeding for less than a month has no impact on IQ

2. Breastfeeding for more than a year has no impact on IQ in infants from high income families.

And, most importantly, the impact of breastfeeding on IQ is dwarfed by the impact on IQ of

Maternal education

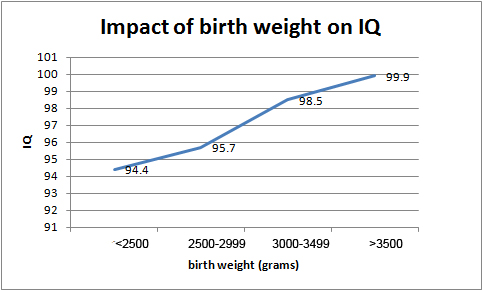

Birth weight

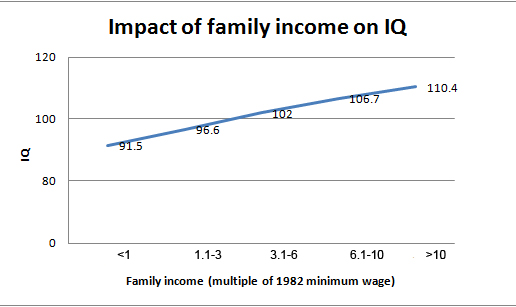

Family income

(All graphs shows babies that were breastfed for 6 months.)

Arguably, if a mother wants to have the greatest impact on her baby’s IQ, she should go back to work rather than breastfeed.

The BBC piece acknowledges the contribution of many variables to IQ:

Regarding the findings – published in The Lancet Global Health – they stress there are many different factors other than breastfeeding that could have an impact on intelligence, although the researchers did try to rule out the main confounders, such as mother’s education, family income and birth weight.

Dr Bernardo Lessa Horta, from the Federal University of Pelotas in Brazil, said his study offers a unique insight because in the population he studied, breastfeeding was evenly distributed across social class – not something just practised by the rich and educated.

Most of the babies, irrespective of social class, were breastfed – some for less than a month and others for more than a year.

Those who were breastfed for longer scored higher on measures of intelligence as adults.

They were also more likely to earn a higher wage and to have completed more schooling…

Dr Horta believes breast milk may offer an advantage because it is a good source of long-chain saturated fatty acids which are essential for brain development.

But experts say the study findings cannot confirm this and that much more research is needed to explore any possible link between breastfeeding and intelligence.

In Brazil the impact of income of breastfeeding rates is very different than in higher income countries. In the US, for example, breastfeeding is correlated with family income; the higher the family income, the greater the likelihood that an infant will be breastfed. In Brazil, breastfeeding rates were highest at either end of the income spectrum, the very poor were as likely to breastfeed as the very rich. Indeed 80% of the children in the study were breastfed at for at least a full month. And that raises an important question.

In this study, the authors assume that breastfeeding in an independent variable that depends almost entirely on maternal desire. But in a country where breastfeeding is the norm, it may be that the duration of breastfeeding reflects the success of breastfeeding. In other words, women who breastfed for only a short duration stopped not because they didn’t want to continue, but because their babies were showing signs of malnutrition. The fact that babies breastfed for less than a month had lower IQ scores at age 30 might be a reflection of malnutrition in the early weeks, not a lack of breastmilk.

This is a good study. The authors followed a large cohort of infants through adulthood. They carefully controlled for confounding variables. They showed that breastfeeding up to 12 months (but not longer) has a small but measurable impact not merely on IQ, but also on educational attainment and income. But the study also has some significant limitations. The authors did not control for the most important confounding variable, parental IQ. They assumed that income and educational attainment were proxies for IQ, but they did not demonstrate that. One third of the study participants were lost to follow up and they may differ in important ways from those who were available for follow up.

Ultimately, though, the authors showed that the impact of breastfeeding on IQ pales in significance to the impact of everything from birth weight to maternal educational attainment to family income.

The take away message should be:

If you want to improve your future child’s IQ, you should stay in school, work hard and get good prenatal care so you can have a larger infant. If you want to improve your child’s IQ slightly beyond that, you can breastfeed. But it may not be only the breastfeeding that impacts IQ but whether the mother can produce enough breastmilk. Breastfeeding a baby who isn’t getting enough to eat may actually be far worse than not breastfeeding at all.