One of the best ways to determine if a profession follows scientific evidence is to determine how it reacts to evidence that contradicts established practice.

Obstetricians were convinced that episiotomies prevented more serious tears, but when high quality evidence showed that to be wrong, the rate of episiotomy plummeted. Pediatricians routinely recommended placing infants to sleep on their stomach to reduce the risk of aspiration, but when high quality data showed that the prone position increased the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), they changed their recommendations to placing infants on their backs and the SIDS rate dropped precipitously.

New, high quality evidence now shows that co-sleeping dramatically increases the risk of SIDS among breastfed infants under 3-4 months of age (Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case–control studies), and the La Leche League is in denial. They base their denial on a “white paper” that insists that the new evidence should be ignored.

The lactivists who wrote this white paper are supremely unqualified to pass judgement on scientific research: 2 are lay people who run parenting blogs, 1 is a nurse, and 2, including Darcia Narvaez, PhD, are an minor faculty in psychology departments. Not surprisingly, they have produced a piece of junk, but to understand why it is so disingenuous, we need to review the study it purports to critique.

The study in question, Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case–control studies, is remarkably rigorous. The authors set out to answer a very specific question: what is the risk of co-sleeping in breastfed babies whose parents do not smoke or drink?

They found:

…[T]he combined data have enabled the demonstration of increased relative risk associated with bed sharing when the baby is breastfed and neither parent smokes and no other risk factors are present (see figure 2 and table 2). The average risk is in the first 3 months and is 5.1 (2.3 to 11.4) times greater than if the baby is put to sleep supine on a cot in the parents’ room (table 3). This increased risk is unlikely to be due to chance (p=0.000059).

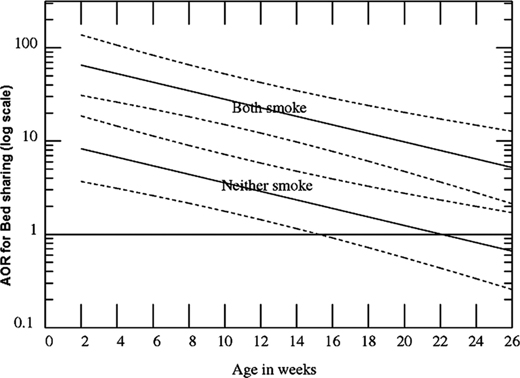

The data is quite robust as demonstrated by the following graph:

The graph shows Adjusted ORs (AORs; log scale) for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome by age for bed sharing breast-fed infants, when neither parent smokes and both smoke versus comparable infants sleeping supine in the parents’ room. AORs are also adjusted for feeding, sleeping position when last left, where last slept, sex, race, and birth weight, mother’s age, parity, marital status, alcohol and drug use.

What is most remarkable is linear nature of the increased risk of SIDS with co-sleeping compared to the risk of SIDS if the baby is sleeping in the parents room, at every gestational age, and regardless of whether or not the parents smoke. Up until the age of 14-15 weeks, co-sleeping always increases the risk of SIDS death.

The authors go so far as to apply Hill’s criteria to their findings:

- Assessment of bed sharing, in the absence of parental smoking alcohol and maternal drug use, as a causal risk for SIDS by Bradford Hill’s criteria31

- Strength of association: Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) for bed sharing=2.7 (95% CI 1.4 to 5.3), p=0.0027, for breastfed infants with no other risk factors. AOR for the first 3 months of life=5.1 (2.3 to 11.4), p=0.00006. These AORs are moderately strong.

- Consistent: Of more than 12 published studies, all but two small ones show, after multivariate adjustment, increased risk of SIDS associated with bed sharing, some combined with sofa sharing…

- Temporally correct: Bed sharing always precedes SIDS.

- Dose response: New Zealand study showed risk increased with duration of bed sharing. Not otherwise investigated.

- Biologically plausible: Bed sharing risk is greatest to youngest infants who are most vulnerable.

- Coherence: The proposition that bed sharing is causally related to SIDS is coherent with theories that respiratory obstruction, re-breathing expired gases, and thermal stress (or overheating), which may also give rise to the release of lethal toxins, are all mechanisms leading to SIDS, in the absence of smoking, alcohol or drugs. Infants placed prone are exposed to similar hazards.

The authors conclude:

… Our findings suggest that professionals and the literature should take a more definite stand against bed sharing, especially for babies under 3 months. If parents were made aware of the risks of sleeping with their baby, and room sharing were promoted, as ‘Back to Sleep’ was promoted 20 years ago, a substantial further reduction in SIDS rates could be achieved.

The white paper touted by the La Leche League condemns the findings of this study and attempts to mislead readers about what the study actually shows.

The authors share two graphs that show how various risk factors (such as infant position, parental smoking and bottle feeding) increase the risk of SIDS. That’s nice, but that’s not what the study is about. The study is specifically about the increased risk of co-sleeping in babies without any risk factors who are breastfed.

The authors insist:

Without consideration of [bedding and temperature], it is not possible to determine that one variable, such as bedsharing itself, is inherently responsible for risk remaining in this study

Really? Is there any reason to believe that the temperature of the bedroom and the blankets on the bed differ between women who breastfeed and those who don’t? Of course not.

The authors continue:

Instead of looking at how each of the variables in the dataset can contribute to risk of infants’ breathing or compromise arousal — the authors focus on whether the act of breastfeeding protects against all risk of SIDS.

Did these women even read the paper? It does not focus on whether breastfeeding prevents all cases of SIDS; it focuses SPECIFICALLY on whether co-sleeping increases the risk of SIDS in babies who are breastfed and finds that it increases the risk by a factor of 5.

The second issue pertains to the risk factors included and not included in the analysis…

Missing from the analysis are other known risk factors: specifically … environmental context (bedding) or infant vulnerability (prematurity)…

But is there any reason to believe that breastfeeding women are more likely to have inappropriate bedding? Is there any reason to believe that breastfeeding women are more likely to have babies who are premature? Of course not.

The lactivists end with this rousing call:

So, let’s stop going around in circles talking about secondary issues and focus on discussion on primary issue: decreasing the risk of SIDS events. If we want to decrease risk of SIDS events, then we must assure infants’ are in the best possible situation to support breathing and arousability.

Apparently they haven’t noticed but that’s EXACTLY what the authors of the original paper are doing. They are looking at an issue that has the potential to dramatically decrease SIDS among breastfed infants.