A new paper in the journal Health Affairs is receiving a great deal of media attention. Although the paper provides valuable data, the authors dramatically overstate the conclusions and leave out critical information.

The paper is Cesarean Delivery Rates Vary Tenfold Among US Hospitals; Reducing Variation May Address Quality And Cost Issues by Kozhimannil et al. According to the authors:

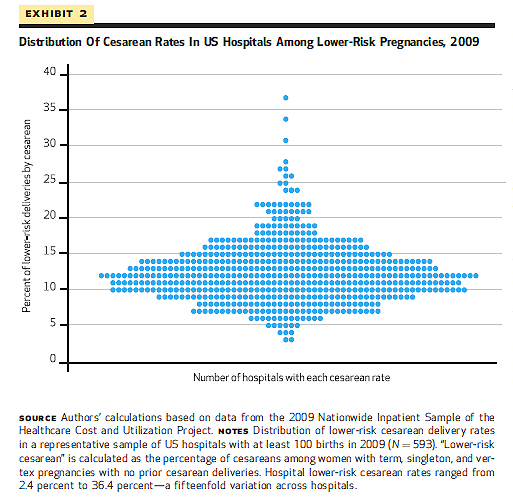

Working with 2009 data from 593 US hospitals nationwide, we found that cesarean rates varied tenfold across hospitals, from 7.1 percent to 69.9 percent. Even for women with lower-risk pregnancies, in which more limited variation might be expected, cesarean rates varied fifteenfold, from 2.4 percent to 36.5 percent. Thus, vast differences in practice patterns are likely to be driving the costly overuse of cesarean delivery in many US hospitals.

Not exactly. To see how the authors overstate their case, it helps to looks at charts that they created.

Yes, it is true that the rate at the hospital that did the greatest proportion of C-section is 10 times higher than the rate at the hospital that did the lowest proportion of C-sections, but a glance shows that both hospitals are outliers. Therefore, that comparison is essentially useless. A far more valuable statistic is the interquartile range, the difference between the 25-75 percentiles. As the authors acknowledge in a subsequent table, the mean C-section rate in 2009 was 32.8 with an interquartile range of 9.4. So fully half of the hospitals had C-section rates in the range of 23.4%-42.2%. That’s still an appreciable difference (double), but very far from the 10 fold difference touted by the authors. In fact, more than 90% of hospitals had C-section rates between 21%-44%.

The same thing applies to the analysis of C-section rates in low risk women.

The authors report that the C-section rate for low risk women varies 15 fold among hospitals, but that is misleading. As the authors acknowledge in the subsequent table, the mean C-section rate for low risk women in 2009 was 12 with an interquartile range of 4.9. Fully half of the hospitals had low risk C-section rates ranging from 7.1%-16.9%. Again the difference is appreciable (slightly more than double), but a very far cry from a 15 fold difference. Nearly 90% of hospitals had C-section rates for low risk women between 6%-19%.

So the national variation in C-section rates is far less than the authors claim. Moreover, the authors commit the same error as do many natural childbirth advocates; they focus on process as opposed to outcome. We shouldn’t be looking for an ideal average C-section rate. We should be looking for the C-section rate that produces the best outcomes. How does the perinatal mortality rate compare between hospitals with low C-section rates and high C-section rates? The authors don’t know because they never looked. Indeed, the underlying (and totally unjustified) assumption that permeates the entire study is that there is no appreciable difference in mortality rates between various hospitals and that, therefore, we can focus in difference in C-section rates.

But perinatal mortality rates do vary appreciably among hospitals and it is critical to include this data. What if the mortality data showed that hospitals with C-section rates below 25% have higher perinatal mortality rates than hospitals with higher C-section rates. If that were the case, the hospitals with lower rates should be chastised, not held up as a model for an ideal, achievable C-section rate.

The authors conclude their paper with the following:

Although some variation would reasonably be expected given differences in patient populations, the scale of the variation in hospital cesarean delivery rates—most notably, a fifteenfold variation among the lower-risk subgroup— indicated a wide range in obstetric care practice patterns across hospitals and signaled potential quality concerns.

But as we have seen, the real variation among hospitals is much smaller making it much less likely that differences are due to practice patterns. Most importantly, the authors are not in a position to assess quality concerns unless and until they look at outcomes, and privilege them above process.