For the last few days I’ve been writing about attachment parenting, a parenting philosophy which has little or nothing to do with the needs of children, and can best be understood as a competition among women looking for validation of their mothering. Simply put, women who pride themselves on making mothering a priority compete as to who sacrifices more for their children.

Lest you think that competitive mothering is restricted to those who place mothering front and center, Marissa Meyer has helpfully demonstrated that competitive mothering is alive and well in the executive suite, though there the rules are precisely the opposite. Instead of competing on who sacrifices more for their children, competitive mothers in the executive suite rig the game so that no other mother can sacrifice more than they do and make them feel bad.

Meyer is the CEO of Yahoo and in her very short tenure thus far she has managed to twice up the ante on mommy competition in the boardroom. First, Meyer made waves by announcing that she would take no more than 2 weeks maternity leave for the birth of her first child.

From the start, Mayer, who at 37 is one of Silicon Valley’s most notorious workaholics, was not the role model that some working moms were hoping for. The former Google Inc. executive stirred up controversy by taking the demanding top job at Yahoo when she was five months pregnant and then taking only two weeks of maternity leave. Mayer built a nursery next to her office at her own expense to be closer to her infant son and work even longer hours.

This week Meyer moved to abolish telecommuting, a practice common at many tech companies:

Now working moms are in an uproar because they believe that Mayer is setting them back by taking away their flexible working arrangements. Many view telecommuting as the only way time-crunched women can care for young children and advance their careers without the pay, privilege or perks that come with being the chief executive of a Fortune 500 company.

Meyer claims to have abolished telecommuting for purely business reasons:

“To become the absolute best place to work, communication and collaboration will be important, so we need to be working side-by-side. That is why it is critical that we are all present in our offices,” Jackie Reses, Yahoo’s human resources chief, wrote in the memo sent out Friday. “Speed and quality are often sacrificed when we work from home. We need to be one Yahoo, and that starts with physically being together.”

Really? Does Meyer have any evidence that the production and quality of work among those who telecommute is less than those who come to the office every day? If she has it, why hasn’t she presented it.

I, for one, doubt Meyer’s ostensible business motivation. I’m afraid that it is about about competitive mothering in the boardroom. Specifically, Meyer wants to ensure that other mothers can’t spend any more time with their children than Meyer spends with hers.

Back in the good old days of conventional sexism, all a professional woman had to do to succeed is to be better at her job than any other man. Now, with mothers in the executive suite, professional women have to better at their jobs than any man AND make sure not to make the boss feel bad that she spends less time with her children than you spend with yours. That’s because women in the executive suite appear to think that the mothering decisions of their female employees are within their purview and ought to be judged with one criterion in mind: “What do her choices mean about my children and me?”

The reality is that Meyer’s decision makes no sense from a business perspective:

UCLA management professor David Lewin said the telecommuting ban is a risky step that could further damage Yahoo employee morale and performance and undermine recruiting efforts in a hotly competitive job market.

A 2011 study by WorldatWork also found that companies that embraced flexibility had lower turnover and higher employee satisfaction, motivation and engagement.

But it makes perfect sense in the world of competitive mothering. In fact, it is the paradigmatic example of competitive mothering in the executive suite. Instead of judging her employees by the quality of their work, Meyer judges them by how they make her feel about herself and her relationship with her children.

Meyer’s action is anti-feminist, but not in the way that most critics imply. Feminists have no obligation to make the workplace more accommodating to other women; they are merely required to offer the same opportunities to women as they offer to men. Meyer’s action is anti-feminist for two reasons. First, because it is the boardroom version of competitive mothering and the terrible propensity women have for criticizing anyone who doesn’t parent in exactly the same way that they do. Second, because it requires extra obligations on the part of other women. Simply turning in a high quality work product is not enough; they must do so without making their boss feel guilty about the amount of time she spends (or doesn’t spend) with her children.

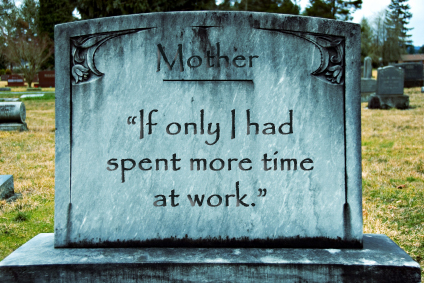

The sad fact is that there are precious few good ways to combine a high powered career and mothering, but some women do manage to do it, whether it is through telecommuting or some other innovative practice. In the world of competitive mothering in the executive suite, that is unacceptable. Those women must be punished for their success in combining work and family so the boss doesn’t have to feel bad that she couldn’t manage to do it, too.